By a Witness of the Times (1967–1968)

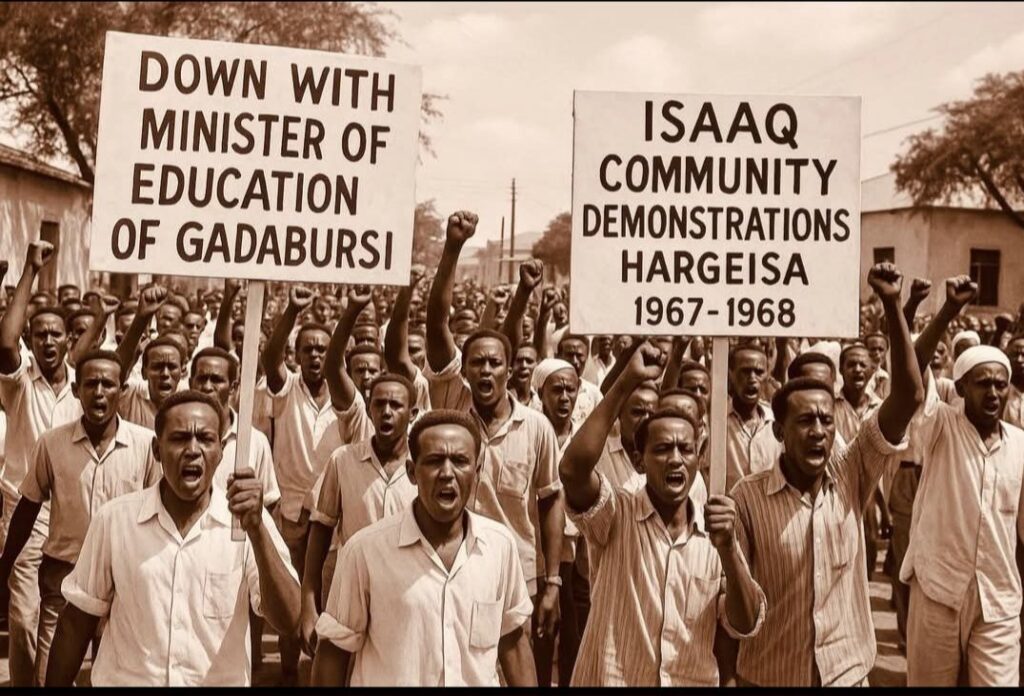

Ayrotv.com-Boon City- In the politically charged years of 1967 and 1968, I was a direct witness to an unsettling period of protest and division in northern Somalia. These were not simple demonstrations—they were organized, persistent, and often targeted. I saw with my own eyes, and heard with my own ears, the slogans echoing through the streets of Hargeisa and Burco:

“Gadabuursi ha dhaco!” (“Down with the Gadabuursi!”)

“Gumaysigu ha dhaco!” (“Down with oppression!”)

What prompted such anger? The answer lies in the political dynamics of the time. Many of the key governmental positions in the northern regions—then part of the Somali Republic—were held by members of the Gadabuursi clan. This was perceived by some as domination or favoritism, sparking a wave of unrest led by segments of the Isaaq population.

To understand the frustration, one must acknowledge the extent of Gadabuursi representation in leadership:

The regional CID chief in the northeast was Cilmi Furre (known as Cilmi-Kabaal).

Maxamed Rashiid (Xeeb-Jire) headed the regional bank.

The Directors of Education for both Hargeisa and Burco were led by Mohamd Abdisalam and Ina Allatuug of Makayl Dheere.

The military had figures such as Cawaale Bustaale and Adayste

The Ministries of Pastoral Affairs and Agriculture were dominated by Muuse Fiin figures.

Public works (BWD) and health departments were led by Reer Nuur and Reer Ugaas, respectively.

Educational institutions like the Beer Agricultural School and the Sheekh School were also directed by Gadabuursi professionals such as Ina Cabdilugweyne and Cabdillaahi Maydane.

Even the national army training center in Sheekh was under Cabdillaahi Faqlle.

These appointments, though likely based on merit and education, were interpreted through a tribal lens. The protests culminated in incidents where entire communities rallied outside courthouses, not because of justice, but because of identity. I recall an incident where Isaaq protesters demonstrated outside a Hargeisa court against the Auditor General, Cali Xuseen (Makayl Dheere), for arresting some men who had embezzled funds from Berbera customs. The accusation was not about guilt or innocence—it was simply that a Gadabuursi official had taken action against Isaaq men.

Such narratives painted the Gadabuursi as colonial overlords in the eyes of some, and for the Isaaq—who were then just beginning to transition from nomadic to civic life—it felt like subjugation. So when Siad Barre took power in 1969, many in the Isaaq community felt they had finally been “liberated.”

But here is my caution:

Do not pass down this narrative of tribal victimhood to your children.

Do not say, “The Isaaq oppressed us,” or “The Gadabuursi ruled us,” or “The South colonized us.”

For tomorrow, that same child may grow up to say, “I used to be a servant.” Such stories foster resentment, inferiority, and division.

Even among Gadabuursi today, I have heard disparaging remarks about educated professionals—scholars and thinkers who should be honored. This is not exclusive to one clan; it is a national pattern. Somali stories that vilify knowledge, discourage progress, or demonize education are not just false—they are dangerous.

We must be vigilant with the stories we tell and the memories we pass on.

The truth is complex. Leadership shifts. Power rotates. But wisdom lies in recognizing that no clan has a monopoly on governance, and no people should inherit bitterness from the past. Instead, we must teach our children a new story—one of unity, equity, and the dignity of all Somali communities.

Reff. Prof. Hassan Warfa