Long before the pyramids rose along the Nile, the foundations of ancient Egypt’s grandeur were being forged in the heart of Africa. Emerging scholarship and archaeological evidence increasingly highlight the profound connections between the Nile Valley’s earliest civilizations and the African societies to its south—including regions in modern-day Somalia. This article explores the historical ties between ancient Somali territories, the Land of Punt, and the rise of Kemet (ancient Egypt), underscoring Africa’s central role in shaping one of humanity’s most iconic civilisations.

The Nile’s African Cradle: Geography and Early Civilizations

The Nile River, often dubbed the “lifeblood of Egypt,” begins far south of its iconic delta. Its two tributaries—the White Nile and the Blue Nile—converge in modern Sudan, but their sources trace deep into the African interior, including the Ethiopian Highlands and the Great Lakes region. Ancient Kemet did not emerge in isolation; it was the product of millennia of cultural, technological, and genetic exchanges with neighboring African societies. Among these were the inhabitants of the Horn of Africa, a region encompassing present-day Somalia, Ethiopia, and Eritrea, which played a pivotal role as a bridge between sub-Saharan Africa and the Nile Valley.

The Land of Punt: Somalia’s Ancient Legacy

Central to this narrative is the Land of Punt—a fabled trading partner of ancient Egypt described in hieroglyphs as “God’s Land” (Ta Netjer). While its exact location remains debated, many historians and archaeologists, including Dr. Kit Nelson and the late Somali scholar Dr. Said M-Shidad Hussein, argue that Punt likely spanned parts of modern Somalia and the Horn. Egyptian records from 2500 BCE detail expeditions to Punt to acquire luxury goods: aromatic resins (like myrrh and frankincense), ebony, ivory, gold, and exotic animals. These resources were not merely trade items but essential components of Kemetic religion, medicine, and royal ceremony.

Key Evidence Linking Punt to Somalia:

- Botanical Clues: Myrrh and frankincense trees, central to Punt’s exports, are native to Somalia’s arid regions and still define its landscape today.

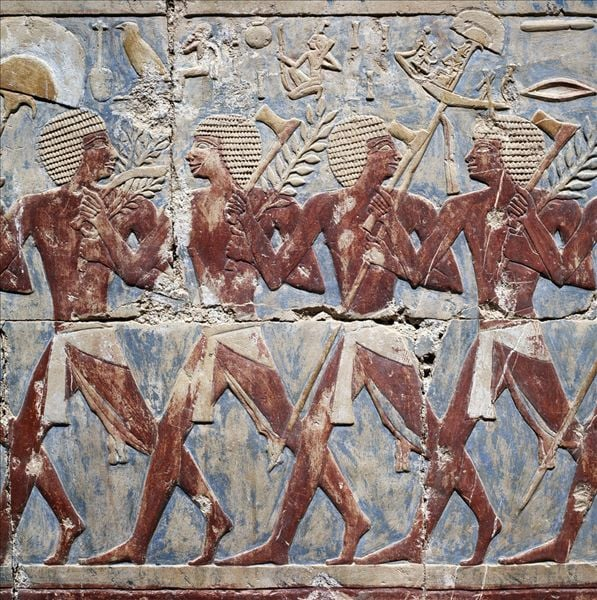

- Cultural Depictions: Reliefs from Pharaoh Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el-Bahri show Puntites with distinct hairstyles, attire, and dwellings resembling traditional Somali aqal huts.

- Genetic and Linguistic Ties: Studies of ancient Egyptian DNA reveal affinities with populations from the Horn of Africa, while Afro-Asiatic languages (including ancient Egyptian and Somali) share deep-rooted connections.

African Innovations That Shaped Kemet

The achievements of ancient Egypt—pyramid-building, hieroglyphic writing, advanced agriculture—were built on African ingenuity. For example:

- Agriculture: The domestication of sorghum and teff, staple crops in the Horn, influenced Nile Valley farming practices.

- Spirituality: Symbols like the ankh (☥) and the worship of celestial deities (e.g., the star goddess Seshat) have parallels in Somali and other African cosmologies.

- Architecture: The use of sun-dried bricks and megalithic structures in ancient Somalia (e.g., the Dhambalin rock art sites) echoes early Nile Valley techniques.

Debunking Myths: Kemet as an African Civilization

For centuries, Eurocentric narratives have sought to divorce ancient Egypt from its African context. Yet, the Greeks themselves referred to Kemet as a “land of black people” (Melanchroes), and Kemetic art consistently depicted its people with dark skin and Afro-textured hair. The civilization’s roots in the African interior—including trade, migration, and cultural exchange with regions like Somalia—affirm its unambiguously African identity.

Conclusion: Reconnecting Africa’s Historical Threads

The story of ancient Somalia and its role in nurturing Kemet is not just about the past—it is a reclaiming of Africa’s intellectual and cultural legacy. As Somali archaeologist Sada Mire notes, “Our ancestors were not passive recipients of civilization; they were its architects.” By celebrating these connections, we challenge colonial distortions and honor the continent’s enduring contributions to human progress.