In September 1888, the HMS Osprey serving in the Royal Navy’s anti-slave trade mission in the Red Sea, based in Aden, intercepted three dhows embarked from Rahayta and Tadjoura on the Ethiopia coast.

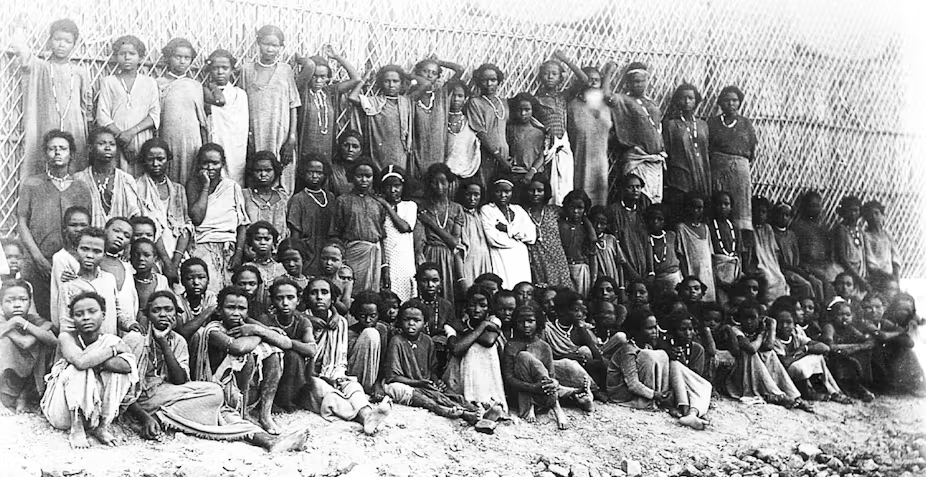

Aboard were 204 boys and girls bound for resale in Arabian markets. Other dhows with young human cargo were also apprehended. The children came from the highland area of Oromia Region of Ethiopia, and spoke the Oromo language.

They had been trekked as many as several hundred kilometres to the coast. The children were taken to Aden and, for a time, were housed and cared for at the Free Church of Scotland mission at Sheikh Othman.

The arrivals, however, were often too debilitated to withstand the harsh climate and prevalent malaria. In 1890, 64 of the survivors were transferred to the Free Church of Scotland’s Lovedale Institution, in Alice, a town in South Africa’s Eastern Cape.

The story is captured in a new book laden with graphs, maps, charts and statistics. But if you like your history as narrative, you’ll have the job of piecing together this extraordinary story written by Sandra Rowoldt Shell in Children of Hope: The Odyssey of the Oromo Slaves from Ethiopia to South Africa.

During the 10 years the children spent at Lovedale they proved to be good students and on good terms with their Xhosa-speaking and English school mates. Four in five survived and left the school as young adults in search of opportunities. They became teachers, shop assistants, carpenters, painters, cooks, clerks.

Fate of Oromo kids

Most remained in South Africa, but 17 earned fares to Ethiopia. A few married and started families. One whose story is traced in the book is Bisho Jarsa who married former Lovedale student Reverend Frederick Scheepers. Their daughter Dimbiti married carpenter James Edward Alexander, and were the parents of South African liberation struggle veteran and academic Neville Alexander.

But most of the Oromo orphans’ lives ended in obscurity or tragedy. Mortality among the returnees was particularly high (33%).

However, the orphans’ stories are not completely lost. Many left behind their autobiographies at Lovedale. They related, in their own voices, their individual ordeals from the time they were captured, sold or pawned, including the tortuously long journeys between their Oromo homeland to the coast. All are rendered in full in the books’ appendices.

Much of Shell’s account delivers the quantitative side of the Oromo story. She followed an assiduous research path to retrieve all possible data related to the orphans, their place of origin, the details of their enslavement and transfer, place by place to various entrepots, the traders and merchants involved, until over a 100 pages later, the Royal Navy’s Osprey appears.

Rich detail

Once in Aden, lengthy asides document the Sheikh Othman mission and its Keith-Falconer school (illustrated by photographs), personal details about the missionaries involved, orphan mortality, age and gender data.

After the orphans reach East London, in the Eastern Cape, we learn a lot about the Lovedale curriculum, comparative performance of Oromo and non-Oromo students (the Oromo did better on average), supplemented with graphs on class marks and percentages, including distributions, gendered results, class positions, and mortality rates, among others (the reproductive quality of the graphs is not very good).

A teacher scandal gets its own sleuthing through the display of doctored photographs eliding the suggestive hands of an Oromo boy on the alleged culprit’s shoulders prior to his dismissal.

Once leaving Lovedale, individuals are traced (thanks to a 1903 questionnaire results unearthed by Shell) that reflect the mixed fortunes of the Lovedale graduates. Though she displays many Oromo group photographs, Shell has uncovered only one individual photograph (the arresting Berille Boko).

A full one-third of the volume is made up of appendices on data variables, the Oromo autobiographies with a place-name gazetteer, an essay by Gutama Jarafo, detailed endnotes, bibliography and an extensive index.

Shell has added a great deal to our understanding of how children were ensnared into the Indian Ocean slave trade, which connected much of the Eastern African interior to Arabia, the Persian Gulf and India. Long after the Atlantic slave trade was snuffed out, the Indian Ocean trade continued almost to the beginning of the 20th century. The Osprey’s intervention and the survival of but a mere quarter of those it rescued suggests that thousands of children’s lives remained enslaved and in misery.

Reff: Theconversation.com